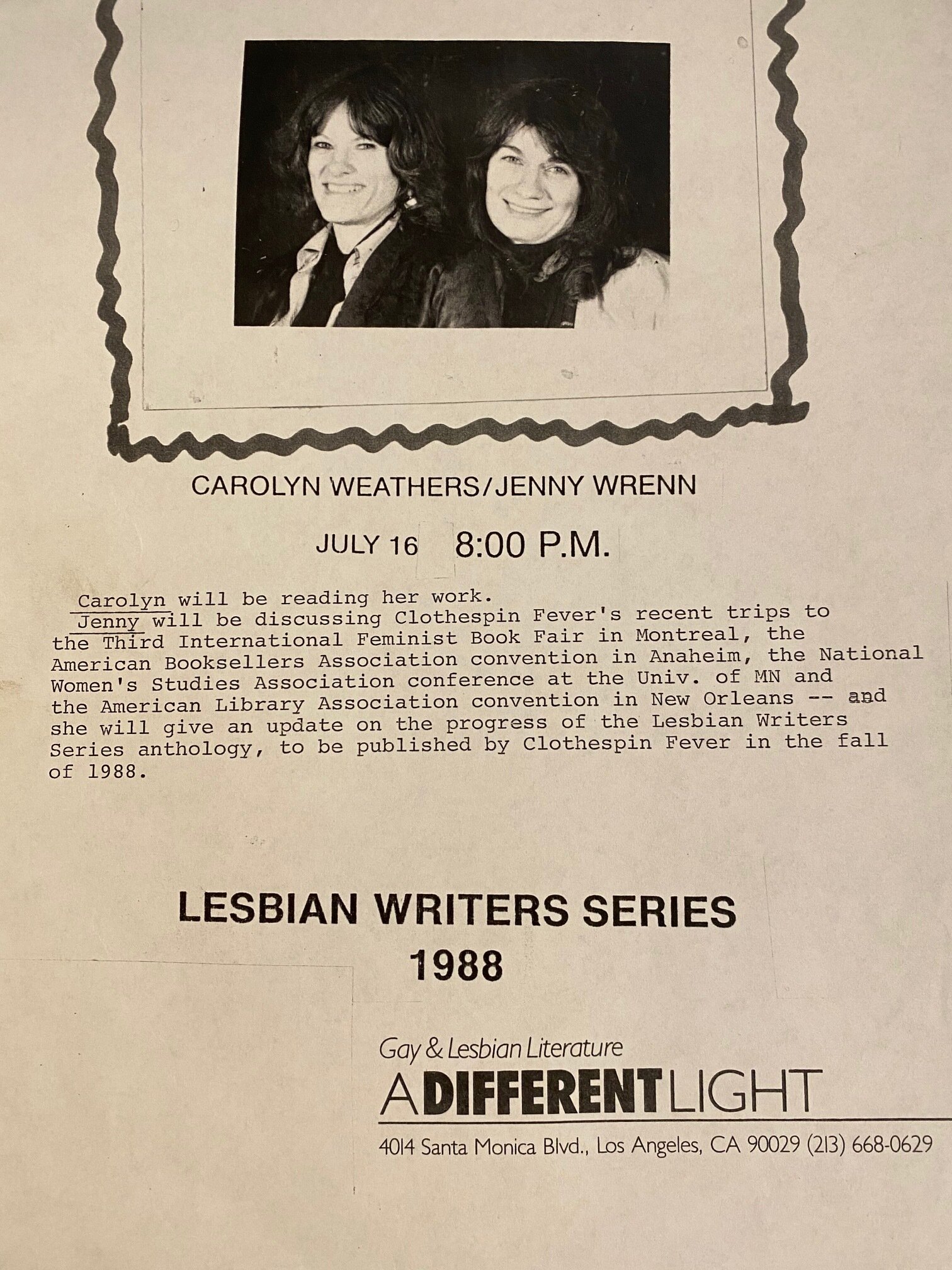

Mazer Archives April 2021 Newsletter | Out of the Archives: Carolyn Weathers + Jenny Wrenn

GOOD OLD CLOTHESPIN FEVER PRESS

by Carolyn Weathers

edited/posted: casey winkleman

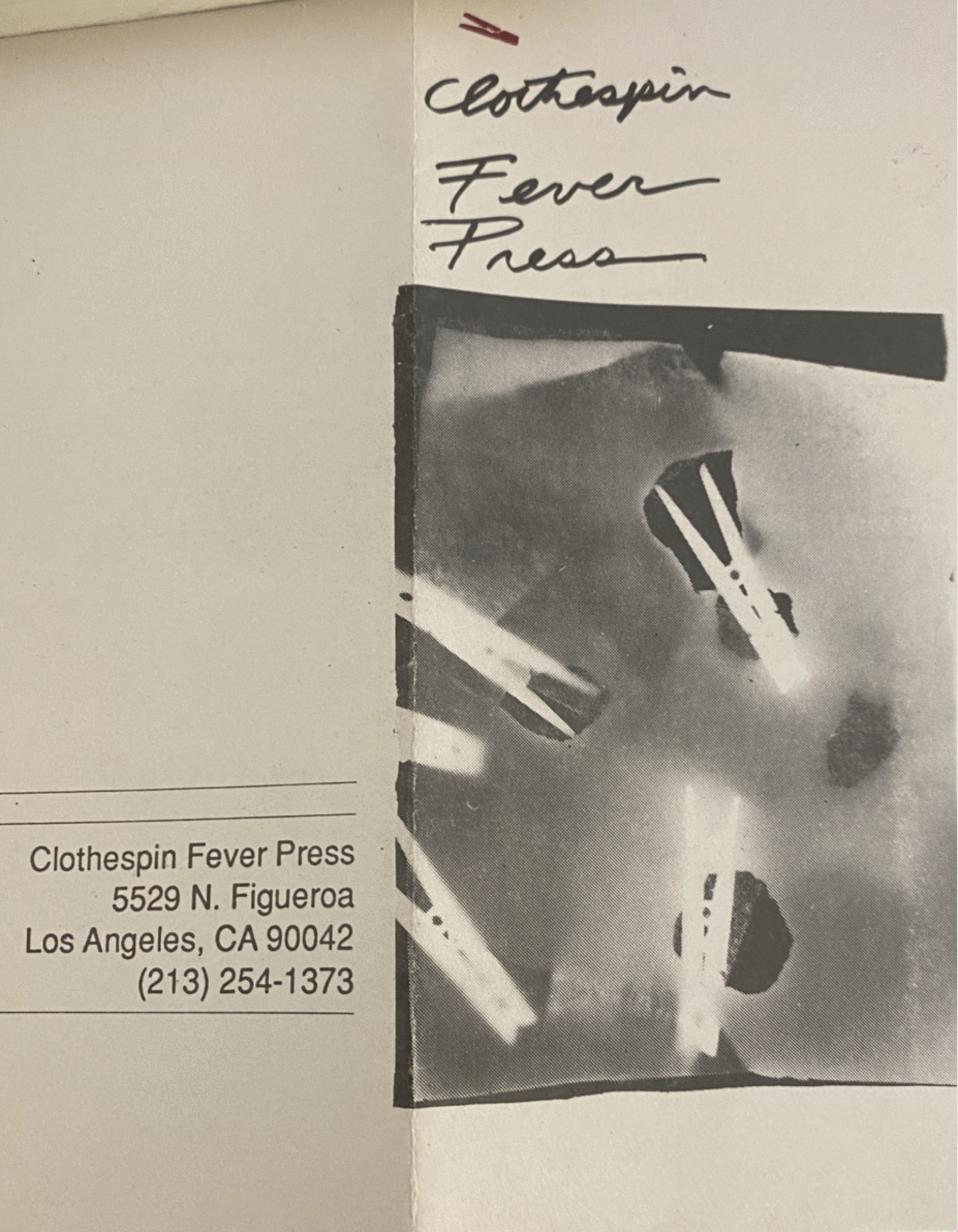

In 1985, Jenny Wrenn and I started Clothespin Fever Press in our home at 5529 N. Figueroa. The place sat on the entire second floor over a variety of small businesses, like Lucky Chinese, mom ‘n pop purveyors of knockout hot ‘n sour soup; a shop run by Inez, who stuffed her shelves with candles, spell books, religious figures and the odd tube of toothpaste; and, next door, a karate school for kids run by a 100-pound woman with a black belt. The yells and thumps reverberated throughout the vastness of Clothespin Fever, as did the party music on Saturday nights from the adjoining Highland Park Masonic Hall. Get hungry and not want Chinese? Just walk across the street to Mexican food place, where the “i” in the sign had gone out, known as Ralph’s Burr-toes.

Clothespin Fever Press, began at a time when Jenny, an artist, and I, a writer, were faced with the dilemma of praise for our works but difficulty in getting many of them hung or published because they were considered marginal— too lesbian for mainstream, not lesbian enough for the issue-oriented. Here were lesbians who made art that might or might not be directly "political," who might address universal issues, but who, at the same time, made it very clear that this work was done by lesbians who were glad of it.

After Jenny heard me read my memoir Leaving at a Los Angeles bookstore, she immediately asked where she could buy a copy. She found it was still unpublished.

She decided to print it herself. She took a class on offset printing press, then rented a noisy A. B. Dick offset printer at the Woman's Building on Spring Street. She printed it in a four-color layout, into which she incorporated artwork and old photographs. She brought the pages home, and we hand sewed it. Leaving Texas: A Memoir came out in 1986 and immediately sold out in its first and second printings.

After the thrill of doing Leaving Texas, Jenny wanted to print her own memoir, featuring her artwork, and titled it Self-Portrait: Viewing Myself as the Adult Child of an Alcoholic and published in 1986, in a limited edition of 250 copies.

Jenny became engrossed with the idea of publishing other lesbian writers. One afternoon she came running into the kitchen where I was boiling potatoes.

“Carolyn, I want to start a book publishing company!”

It would be a publisher of lesbian writers. They could write anything they wanted, from their first trip to a lesbian bar to a story about their dog’s trip in space to visit the Moon Doggies.

“We could publish what we like, markets be damned!”

She had me hooked.

But what to name it?

Jenny went into one of the nooks and came out with a twelve by eight-inch book. It’s front and back covers were Masonite, fastened together with carriage bolts, adorned with clothespins. The clothespins were held in place by nails hammered through from the inside of the cover. Inside were pages of Jenny’s artwork on handmade paper. Jenny had spray painted everything white. The year before, she had shown it at the Huntington Library’s exhibition of book art.

She called it White Clothespins.

Welcome to Clothespin Fever Press!

We sent out calls for submissions, and submissions started coming in.

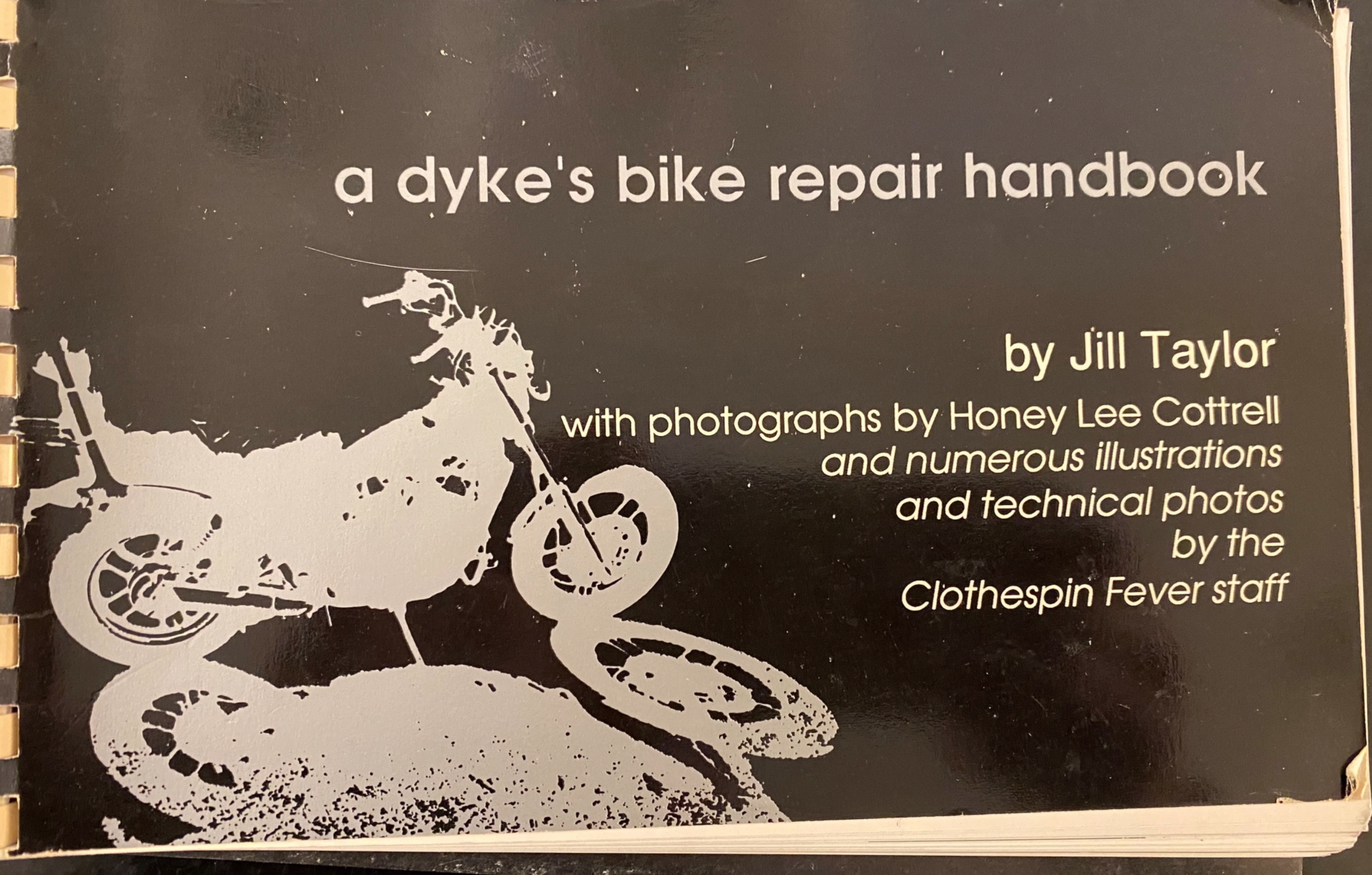

Traditional and experimental. Poems, short stories, short memoirs, mysteries novels, erotic poetry. A book of poems in English and French by a Puerto Rican/German American lesbian poet. A book of subjectively impressionist short stories. A witty and affectionate lesbian parody of a noir novel. A deliciously written book of lesbian erotica. A mesmerizing non-fiction account of a lesbian's experience in a mental hospital.

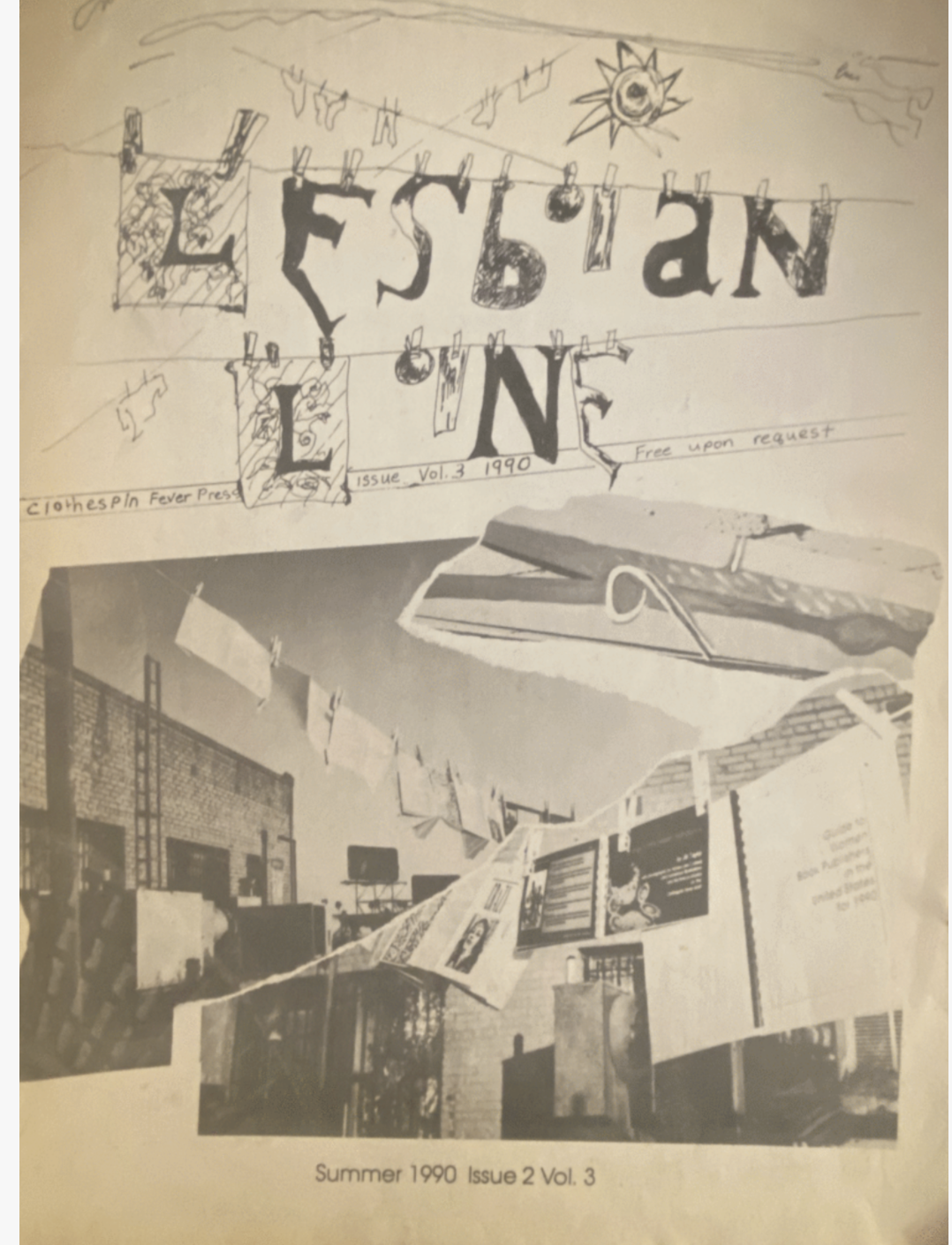

Jenny printed Lesbianline, an occasional paper devoted to the feminist and lesbian book publishing world, with small doses of academic and public library news. Each issue was replete with photographs and drawings. It was also our catalog. Its cover featured a photograph of our books hanging by clothespins and a clothesline strung across our roof. The last page of every issue listed where to find lesbian books across the nation.

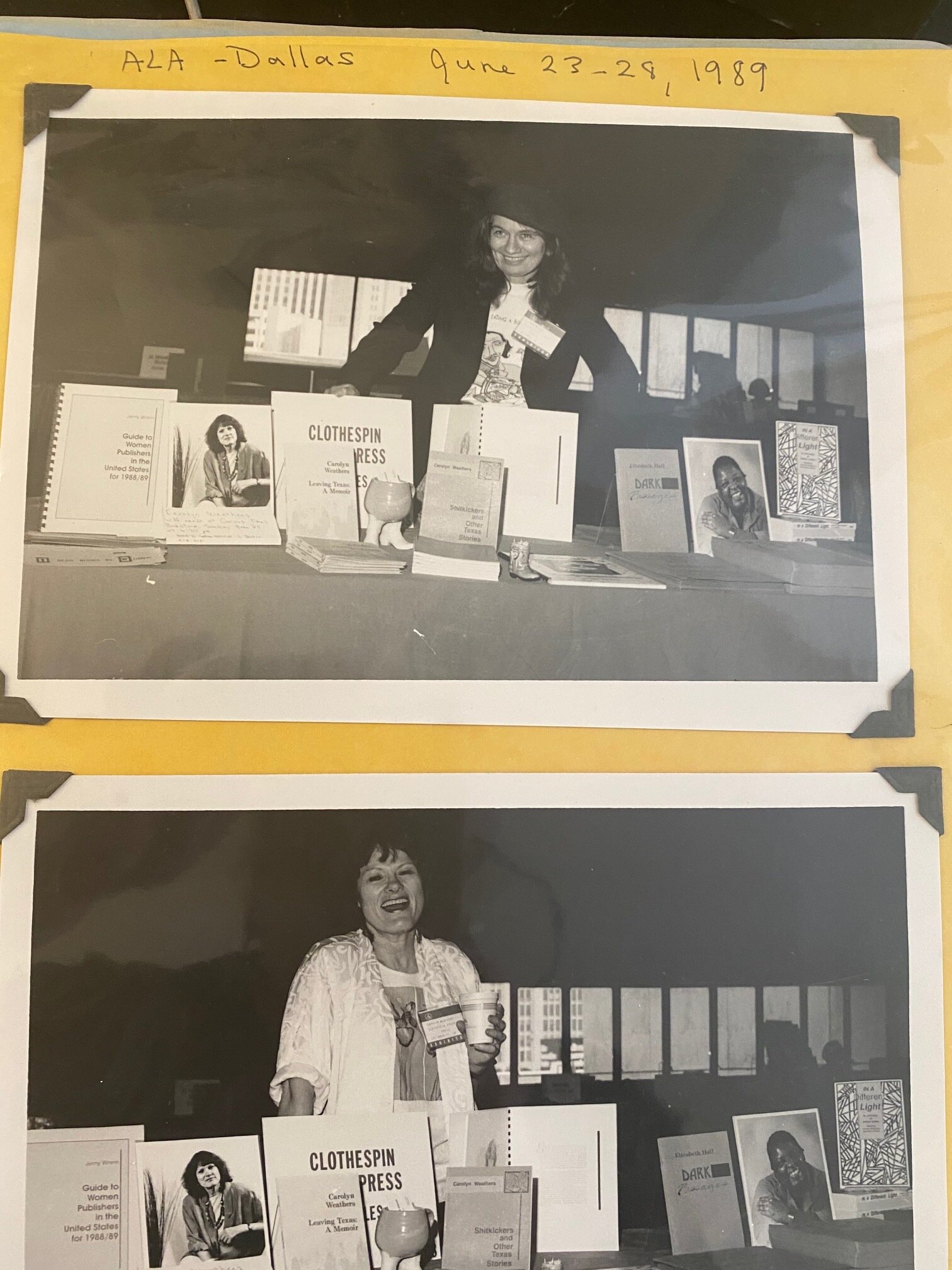

We attended the yearly conventions of the National Women’s Studies Association (NWSA), the American Library Association, and the American Booksellers Association. The booksellers display at the NWSA was thrilling. Here women from the Feminist Bookstore News and lesbian feminist book publishers reconnected, sold our books, and met and partied. Crossing Press, Mother Courage, Seal Press, Kitchen Table Press, Woman in the Moon, Spinsters Ink, Cleis, New Vistoria, AlysonBooks, Firebrand Books, Naiad, Onlywomen Press, Clothespin Fever Press.

Along with our books, Jenny and I were not above hand-painting uniquely artistic, one-of-a-kind shoes and selling them on the side at the American Booksellers Association. (They sold like snowballs in hell.)

By now, we had left the rented offset printer with its homemade but artsy style to buy a Mac II computer and desktop publishing software to do our own typesetting and formatting. We left that and hired professional book printing companies.

A big truck would drive up and unload the books, flats and flats of book boxes, lined up in the Clothespin Fever Press long hall.

Up and down the length of this hall, walls were covered with art and found art. Crepe paper hung across the ceiling. A dusty fake Tiffany lamp hung next to a rolling Kleig light, brocade tapestries gone to seed shared the wall with a six-foot plastic pencil. As might be expected from a duo whose large reproduction of a Faberge egg sat next to a green and yellow lava lamp, or a free-standing, four-foot-high plastic blow-up of Scream next to a eight-foot reproduction of Botticelli’s Three Graces from Primavera, held up by giant wooden push pins painted in deep blue, greens, reds and yellows.

Books tumbled out of bookcases and into piles on the floor. Dogs snorted and snored next to spray-painted sheet metal and Jenny’s neon art.

In these halls, we held receptions, salons, and BYOA (Bring Your Own Art) parties. One Saturday night at a BYOA party, twelve of us women went out into the hall and hollered and danced to the raucous music coming from the Masonic Hall next door.

Another weekend, Jenny and I rented the sumptuous 1922 silent movie adaptation of Oscar Wilde’s Salome. Produced and starred in by Alla Nazimova, it was a decadent and now campy silent movie with overacting. Alla Nazimova was a leading actress of the day and a notorious lesbian (and Nancy Reagan’s godmother, whose mom was best friends with Nazimova). The movie featured gay and lesbian actors in all the bit parts. We rented this movie in the 1980s before VHS. It came in a can and we showed it on a sheet strung across one of our rooms.

Afterwards, we in the lush hall of Clothespin Fever Press saluted this enterprise, and the very idea of it, with Hawaiian Punch, cheap wine and fish sticks.

Jenny described us as artists who were like conductors, guiding and helping bring forth the work of other artists as well as ourselves.

Clothespin Fever is in the great tradition of women publishers and other small presses in that it exists because it has something to say and belongs to the vanguard, doing the most important work. They are not in the business to be making money, and we sure damn didn’t.

Small output, limited budget, limited time was our world. Jenny and I were the only staff, unpaid ones at that. Everything went back into the press. We were so small that we weren’t big enough to qualify for a Small Business loan. We read all submissions, kept accounts, wrote all correspondence, did advertising and layout, proofing and shipping to distributors. When we received mail addressed to the art director, marketing director, production manager, director of advertising, business manager, publicity director, director of the graphics department, vice-president in charge of sales, fiction, non-fiction or poetry editor, business manager or graphics department, it was easy to sort them out and put them on the right desk.

The whole time we ran Clothespin Fever Press and did our art, we continued our positions as librarians.

Clothespin Fever Press books garnered awards and great reviews. Articles were written by and about it. Clothespin was instrumental in paving the way for lesbian authors to get published. But it was not a financial success. It cost Jenny and me everything we had. I had put my inheritance into the pot, and Jenny mortgaged the house she had inherited, all to pay for just one more press run.

Good old Clothespin Fever Press, unable to continue the strain of two people running an undercapitalized company, went bankrupt in 1996.

We were one of several small press book publishers and independent bookstores who went broke and closed their doors as the heyday was ending.

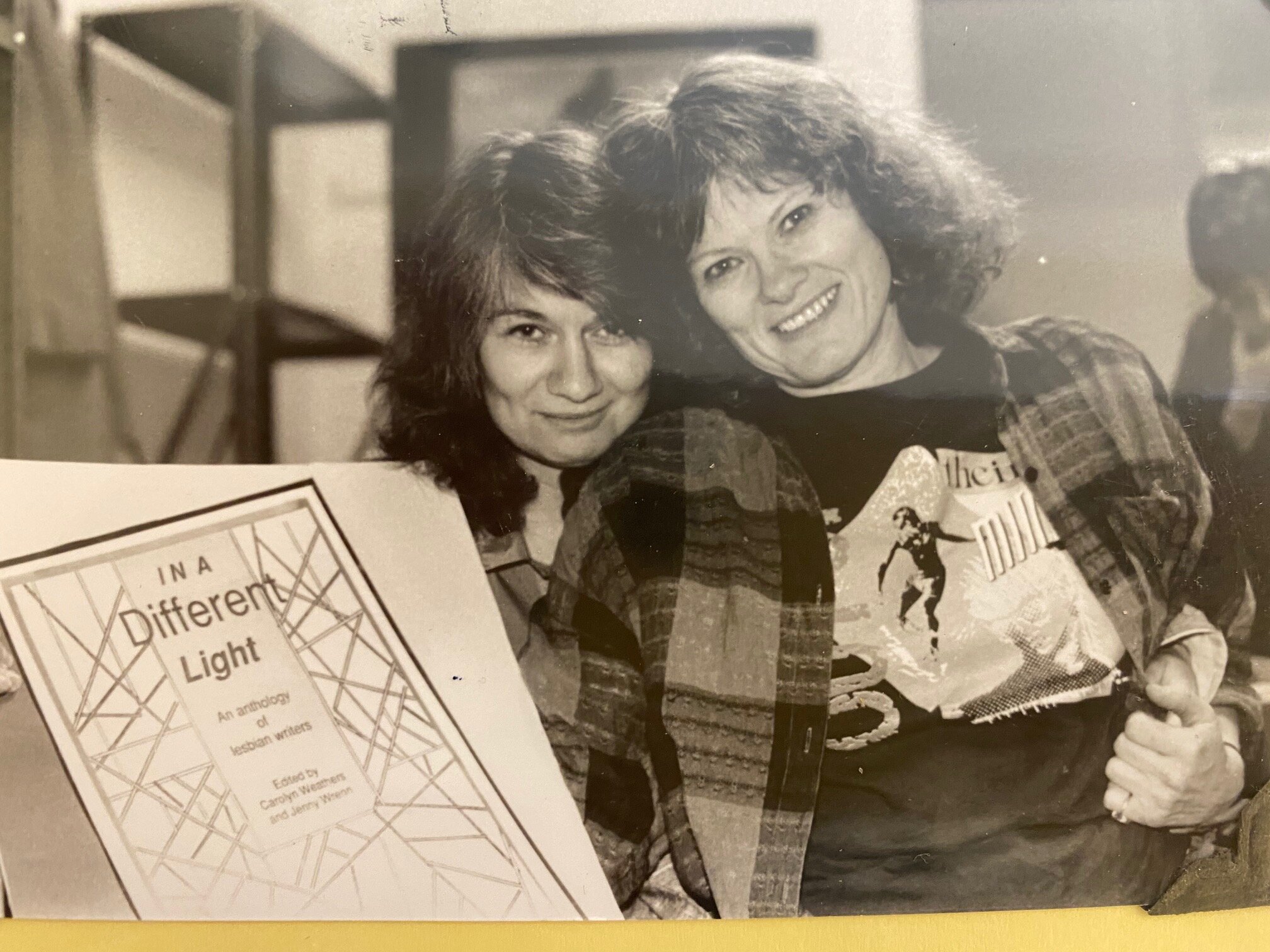

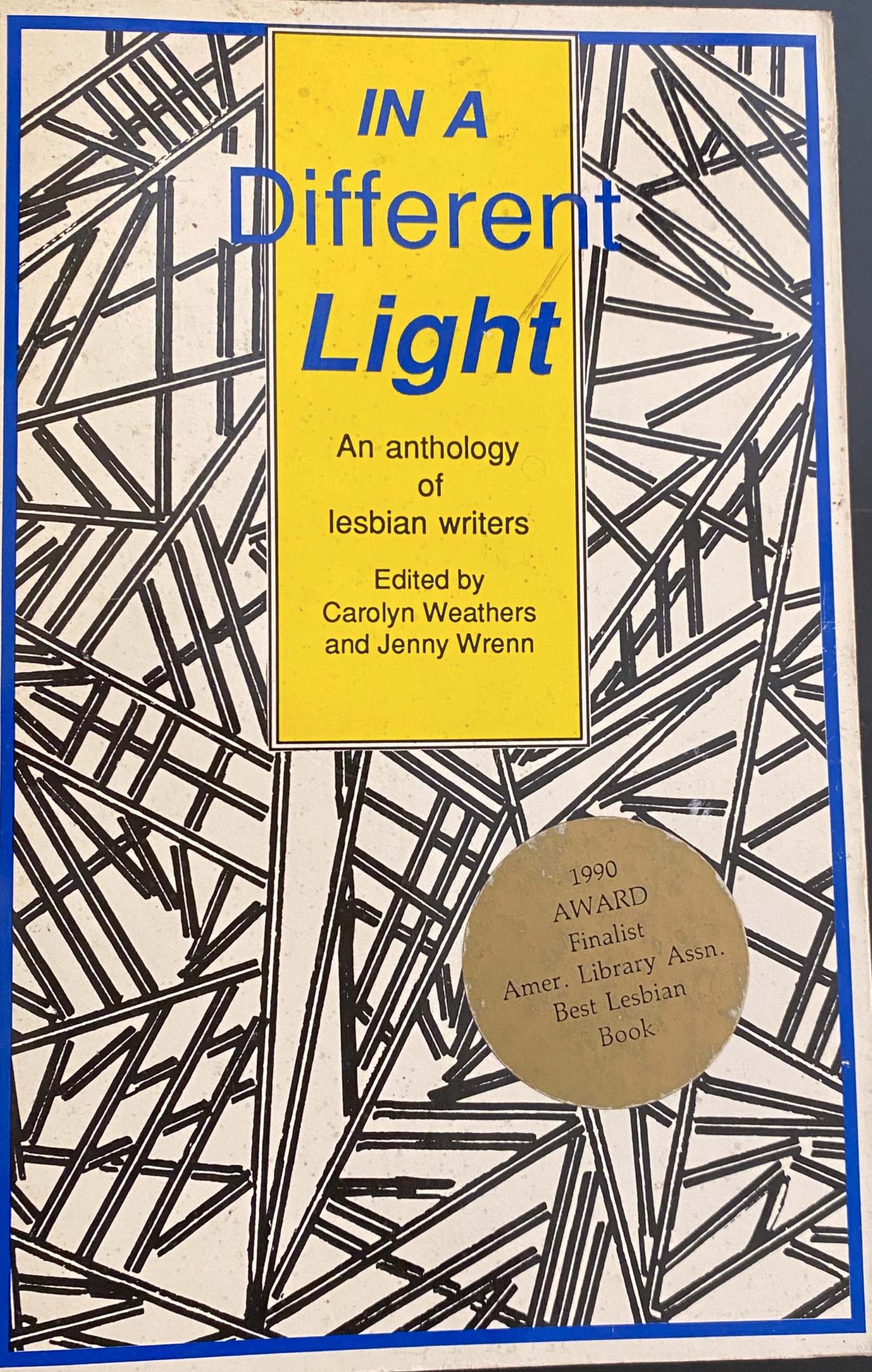

In a Different Light: an Anthology of Lesbian Writers was a finalist for the American Library Association’s Best Lesbian Book for 1990. Terry Wolverton’s poetry Black Slip was a nominee for the Lambda Book Award. Loss of the Ground-note: Women Writing about the Loss of their Mothers (edited by Helen Vozenilek) was a Susan B. Koppelman award winner for best anthology, and a Quality Paperback Book Club Selection. Jenny’s Directory of Women-Owned Publishing Companies, which had included publishers too small and unrecognized to appear in most directories was named a Booklist, a publication of the American Library Association, a Best Reference Book pick for 1989.

22 books, 45-plus great writers. Not bad for a press that started out on a rented offset printer, and with no money.

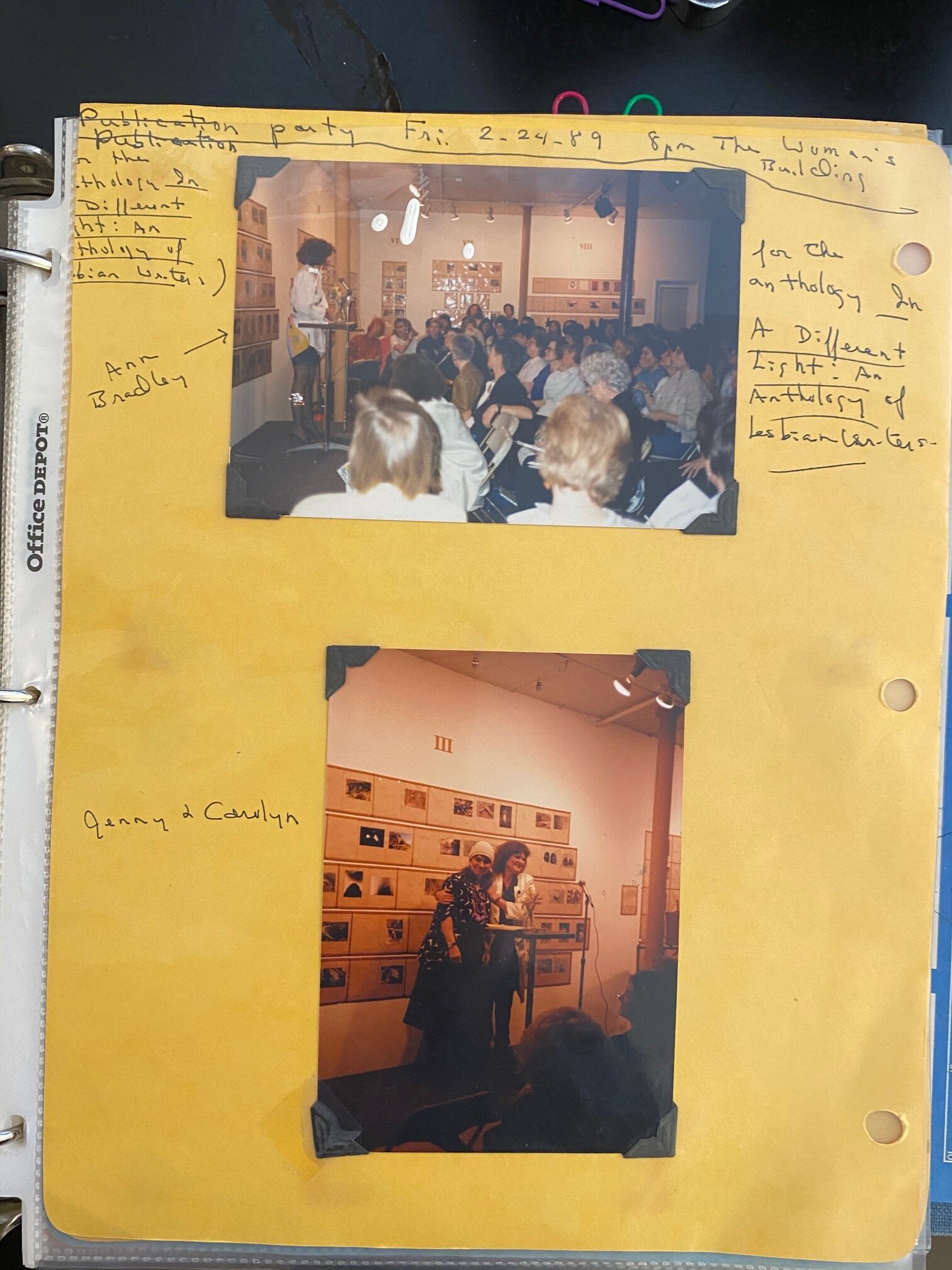

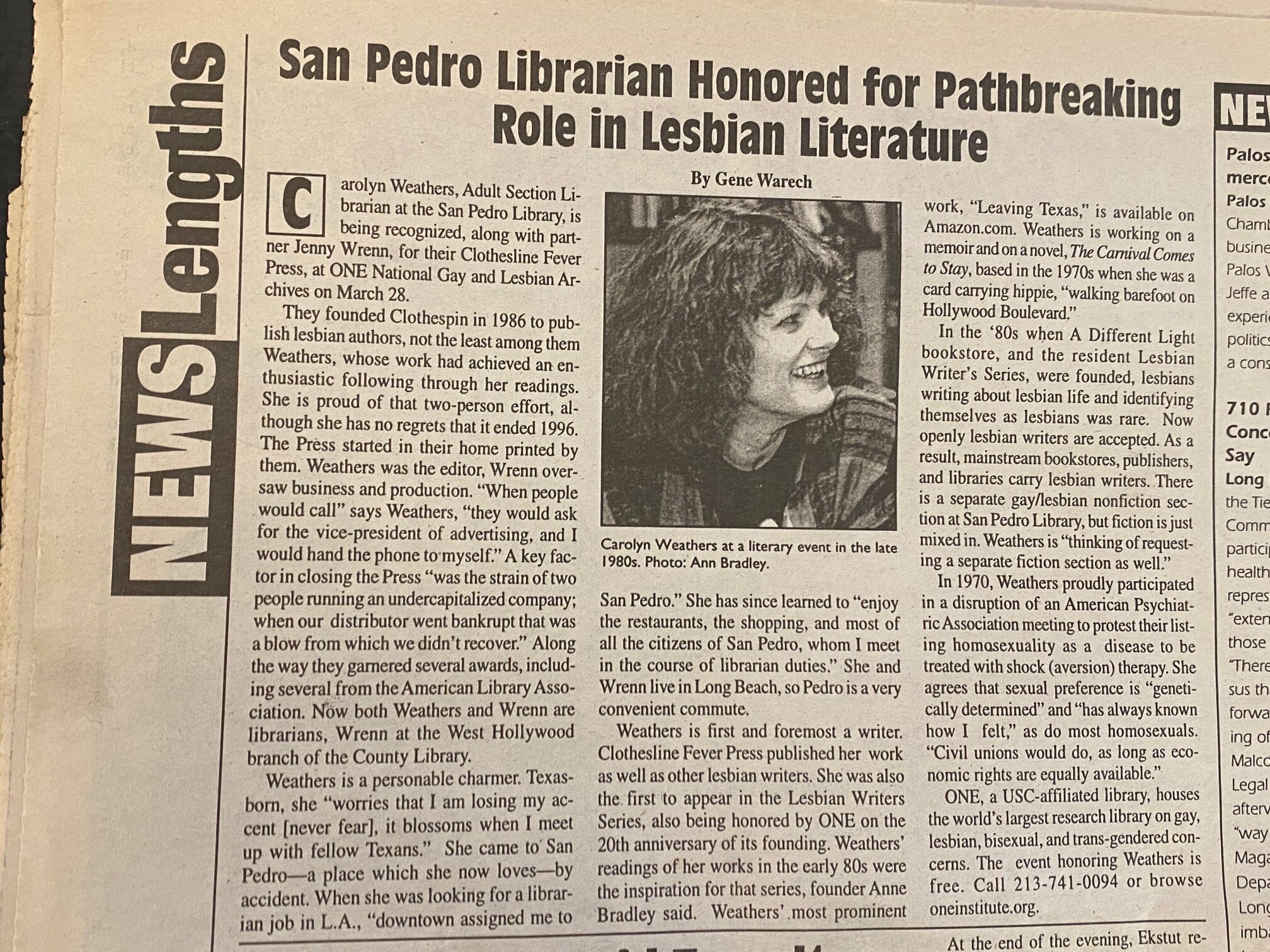

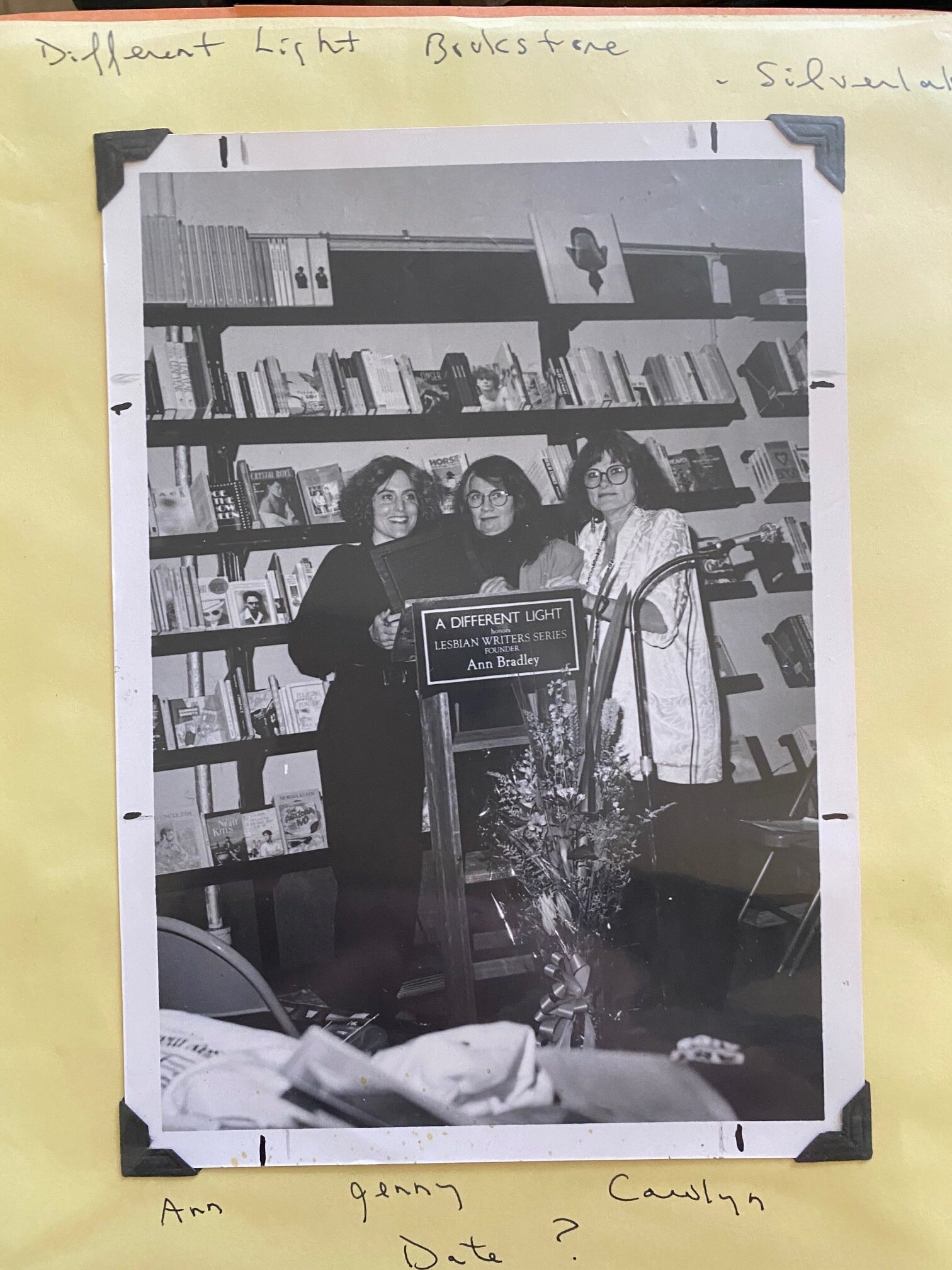

In a Different Light: an anthology of lesbian writers, was a runner-up for the American Library Asssociation’s Best Lesbian Book for 1990. In a Different Light, was an anthology of writers from the first the five years Ann Bradley’s of Lesbian Writers Series (1984, 1985,1986,1987, 1988), at the flagship store in Silverlake.

In 1990, the spectacular launch party for In a Different Light was at the iconic Woman’s Building on Spring, where Jenny printed Leaving Texas on an offset printer in 1985. Ann Bradley inaugurated it. All the anthology writers read from their works. The place was packed. The food was delicious, the with and with/out punches were delicious. And the company was excellent.

Jenny described running Clothespin Fever as the greatest experience of her life. The reward was in making something out of nothing. She said, “Along the way, many have asked me, ‘Why do it? Why?’ A patron came into the library where I worked, looking for books on mountain climbing. I’d read almost all the titles he mentioned.

“If you ask a mountain climber why take so many risks just to climb a mountain, the answer is—to do it. In nearly every mountain climbing book I’ve ever read, the biographies of the climbers showed an unconscious and almost uncanny preparation for the adventure they would embark on as adults and the frequent sacrifices they made along the way for what was ultimately a reward in itself.”

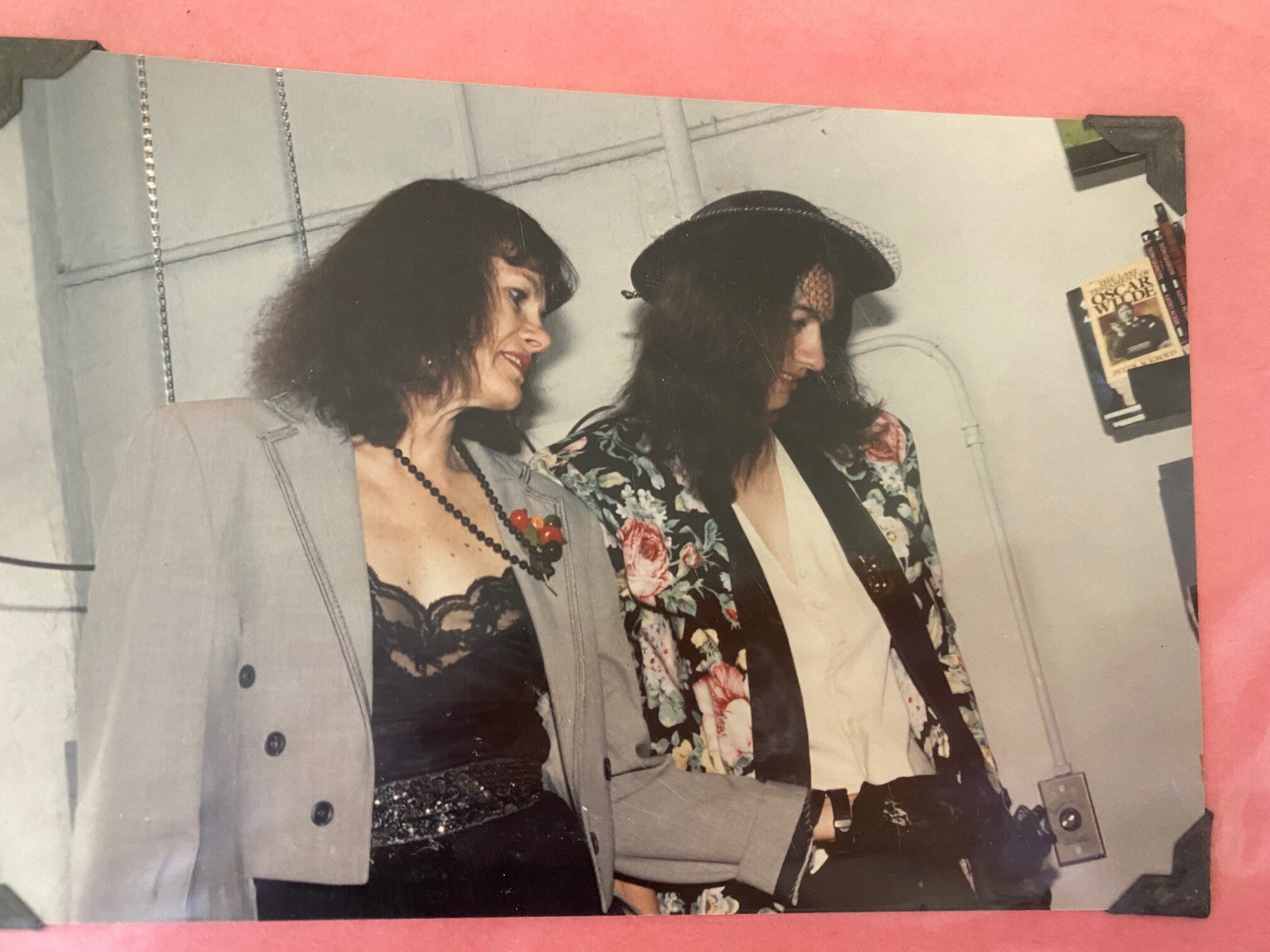

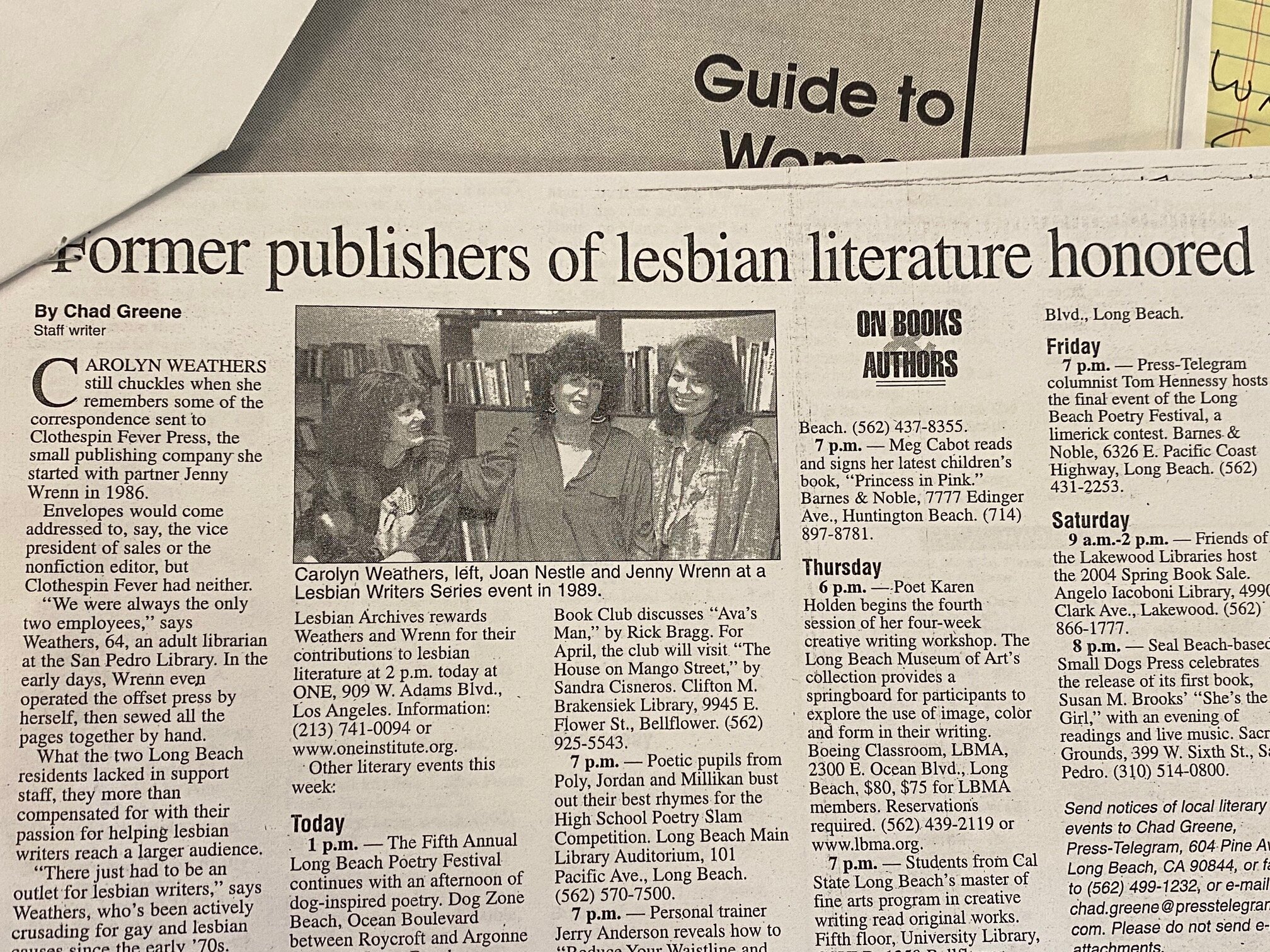

In February 2004, ONE Archives held an event called “Twenty Years of L-Words” to honor Ann Bradley, the founder of the Lesbian Writers Series. There was also a special recognition of Clothespin Fever Press.

After the awards ceremony, Marie Cartier took the open mic. She was the last author Clothespin published, and we had squeaked her book out with our last gasping dollar, and, indeed, could not bestow the cover art on it that we did with our other books. Marie commented on the jolt this book, I Am Your Daughter, Not Your Lover, gave her career. She has since gone on to found Dandelion Warriors Foundation for the survivors of incest, and to produce plays, teach seminars at universities, publish other works, perform at Highways. Marie praised the domino effect of this book on her life and career. She looked at Jenny and me and whispered, “Thank you!”

That’s what Clothespin Fever Press was all about.

In 2014, ten years after this event, I was driving around some of my old haunts on what I called a nostalgia drive. One of my visits was to 5529 N. Figueroa. The door was open. I climbed the stairs and asked the people if I could have a look around, that I had lived 20-30 years ago.

The two women and one man’s reaction were astonishment. Their eyes lit up. They smiled and asked if I was one of those women who had lived here at that time who had a fabulous arts society here.

That wasn’t quite how it really was, but to realize that the time of Clothespin Fever Press had become a myth, a Camelot, passed down from one stranger to another who came to this place, brought a catch to my throat. So I thanked everyone, walked down the stairs and back my car. I drove away from my nostalgia trip back my now home in Long Beach, but the nostalgia trip didn't leave me.